In this three-part series we will go over my take on influence mapping. In this post, Part 1 of the series, we will look at some of the principles involved and explain how to create the influence map. In Part 2 we will cover how to work the influence map to evolve the decision landscape. Finally, in Part 3, we will bring it all back together, looking at examples and summarizing the principles involved.

Intro

In the 1964 presidential election Lyndon B. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater by a historic 14 million votes. Some Goldwater supporters were so crestfallen that they left politics altogether, never to return. Others, such as political strategist Morton Blackwell, turned to digging into what exactly could have gone so wrong.

In his piece, “The Real Nature of Politics,” Blackwell references Goldwater’s campaign slogan, “In your heart, you know he’s right.” (Which was famously countered with, “In your guts, you know he’s nuts.”) Goldwater’s slogan, Blackwell argues, assumed that you win by having better arguments than the other side.

Blackwell now refers to such thinking as the “Sir Galahad Theory,” which might better be described as a fallacy. The Sir Galahad Fallacy then is to assume that others will be influenced by your argument if you just make your case well enough.

Unfortunately, that’s not how it works. Facts do not influence; or, as narrative warfare theorist Ajit Maan puts it, raw data is not inherently influential—it must be “storified.” This is true for a variety of reasons. First, it can be difficult even getting agreement on just what the “facts” are. Second, even when there is agreement on the facts, people still emotionally tag them in different ways, interpret them through different lenses, and then ground decisions in different underlying values.

In other words, information isn’t conveyed—it is always interpreted and weighted in certain ways, filtered through a prism of social (indeed, almost tribal) dynamics. Trying to influence while ignoring such dynamics is a fool’s errand. To influence, then, you need to not only know your facts but, more importantly, you need to study influence itself. To quote Blackwell, “Being right in the sense of being correct is not sufficient to win….”

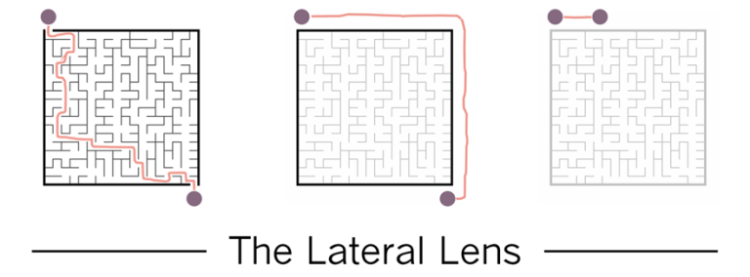

A helpful tool here is influence mapping. There are a variety of flavors of this concept out there. My favorite is from DeLuca’s excellent book, Political Savvy, which I’ve altered by pulling in some additional ideas. The process is divided into three parts, based on the three phases of a game of chess: the opening, middlegame, and endgame. It’s not a perfect analogy, but it works:

The opening is for setting the stage. The middlegame is where most of the innovative play occurs. The endgame, if needed, is about putting on the final touches.

Let’s get started.

The Opening Game

To do influence mapping well, you need to learn some core principles. Here is the first: Influence is just conversations. That’s it. Consider these definitions, from negotiator Kwame Christian. A “negotiation” is just a conversation where somebody wants something. A “conflict” is just a conversation where there is a disagreement about something. A “difficult conversation” is just a conversation you’d rather not have. The bottom line, of course, is that they’re all still just conversations!

This brings us to the second core principle: Conversations are had with people. Sounds obvious, but remember, facts don’t influence people. Influence has to do with stories, relationships, and how information is emotionally tagged. People have egos and self-esteem needs. They care about image and status. They often will not support a decision if they do not feel their position has been heard and taken into account.

There is a social dynamic to this as well, and this is represented in next principle: Do not influence alone. Also: Focus on the relationships. Don’t treat negotiations as two-party affairs. Whoever the D is, the ultimate decision maker, they will make the decision in question in some context or milieu, a “decision environment” composed of certain information and other key players or stakeholders.

Influence then is a team sport. We are so used to functioning as teams for so many aspects of our work that it’s a bit surprising we still so often try to influence without help. This is misstep. The very process of creating an influence map prevents this. The point of influence mapping is to discover who should be having conversations with whom (and in what order!) to have the optimal effect.

Step 1: List the Key Players

An influence map is made relative to some decision. What is the decision you are trying to influence? And who has the authority to make this decision? This person, whom we’ll call the “D,” is ultimately whom you’re trying to sway. If you don’t know who this person is, finding out is your first goal. You might have to hold some meetings and ask around.

As we saw above, it’s not just about you and the D—there is a hidden dynamic at play. The process of mapping will help iteratively reveal this to you. Start writing down names. As James T. Brown suggests in his excellent book, The Handbook of Program Management, it is often helpful to look for stakeholders in the following places.

Cast a wide net here. In general, it is better to identify more people than necessary than to leave important players out of the picture. Brown illustrates this with a matrix he uses in lieu of influence mapping, shown below.

Here, after you list stakeholders you rate them on two variables with three levels each: their position on the matter at hand (whether they are for it, indifferent, or against) and their level of power or organizational influence (low, medium, high). This allows you to position stakeholders within the matrix. Any with a cell score of four or greater, Brown says, needs an additional level of stakeholder management.

To identify the right stakeholders to include, it is helpful to start asking and answering certain questions. For instance, when you find out who the D is, try to learn how they tend to make decisions. Whom do they tend to listen to? Who has the D’s ear? Who is on the D’s team? Whom do you know who knows these other people?

Borrowing a phrase from Alan Weiss, if the person you’re meeting with is functioning as a “gatekeeper” for the D, and only wants you to go through them, then how can you better influence the gatekeeper? And who else can be a path to the D to help you get around the gatekeeper?

If you’re working with a small group, then you can ask and answer such questions collaboratively.

Note: This can be done with paper and pencil but is easier to do digitally. I personally use Excel for the spreadsheet and PowerPoint for the map. (If you’d like a copy of the templates shown here, complete with the icons ready to be dragged and dropped for the mapping, feel free to email me at charles.lambdin@gmail.com.)

Step 2: Cast the Key Players

At this point you should have a list of key players. In addition to the D, whom you identified above, you are now going to cast stakeholders as being either Coalition, Opposition, Unknown, or Settlers, defined below. “Settlers” is a concept I borrowed from April Mills’ book, Everyone Is a Change Agent. This is anyone already working in this space or on this issue who might feel like you are invading their turf. Since they might resist your efforts if you do not consult them, it is important that you build relationships with them and enlist their support.

You may not know everyone’s “role” at this point, and that’s fine. It’s still important to just fill in what you think is the case. This information might change as you work your map. That just means you’re learning. For now, most people might even be Unknowns. That’s also fine. In general, just creating the map helps you work the map. The meetings you will schedule will iterate your map, filling in more data as you go.

Step 3: Rate Level of Support and Org Influence

Similar to Brown’s Stakeholder Assessment Matrix (shown above), you will now rate the stakeholders listed on two variables: their level of support for the decision in question and their level of org influence.

Go ahead and include yourself in this as well. Some approaches to influence mapping place “You” at the center of the map. Not this one. Go ahead and rate yourself. Hopefully you are in favor of the decision you would like to have made 😊. Your level of org influence, however, is likely lower than the D (or you probably would not be doing this). Together this means you will typically be on the lower righthand side of the map. The scales to use are explained in the spreadsheet shown below.

Once you’ve done your listing, casting, and rating, then you can create your first map. The legend below shows the symbols that represent the casting on the map.

The ratings locate each player in the matrix above left, with level of support plotted on the x axis and level of org influence on the y. In the present example we have the D, one Coalition, two Unknowns, three Settlers, and You. Using the casting and ratings depicted in the table above, the map would now look like the image below.

Step 4: Relationships and Permission

Now it’s time to add the relationships of interest between the key players in the mix. Here you will use arrows to depict who is influencing whom in this situation. When added to the map, the arrows build out the possible influence paths from you to the D. The main point of this exercise, after all, is to build a coalition to indirectly influence the D on your behalf!

Here you will rate the “permission” of each relationship, a key concept from nonverbal behavior expert Michael Grinder. Permission, in brief, is one person’s level of receptivity to another’s influence.

Please note this is not the same thing as rapport. You might have great rapport with someone who still isn’t open to hearing from you on a particular topic. And this can be true for a variety of reasons. Maybe they don’t see you as credible on this specific subject. Maybe your role is too different from theirs. Maybe your pay grade is too different from theirs. Whatever the reason, while establishing rapport can make a difference, it’s not sufficient to influence. (In fact, it’s not always necessary either.)

Permission is represented in the map by the thickness of the relationship arrow. If using PowerPoint, each rating becomes the literal width of that line. For example, a relationship with a permission rating of 7 is now a line with a width of 7 pts. (Neat, huh?) Adding this new data, you now have a complete influence map:

Just glancing at this, a few things are suggested that may have not been readily apparent before. Diving in, however, brings us to….

…as in, to be continued in Part 2.

“For example, a relationship with a permission rating of 7 is now a line with a width of 7 pts. (Neat, huh?)” As someone who is continually looking at better ways to visualize lots of data in easily digestible ways, this is very neat. And I plan on stealing it with pride 😉 Looking forward to reading parts 2&3

LikeLiked by 1 person